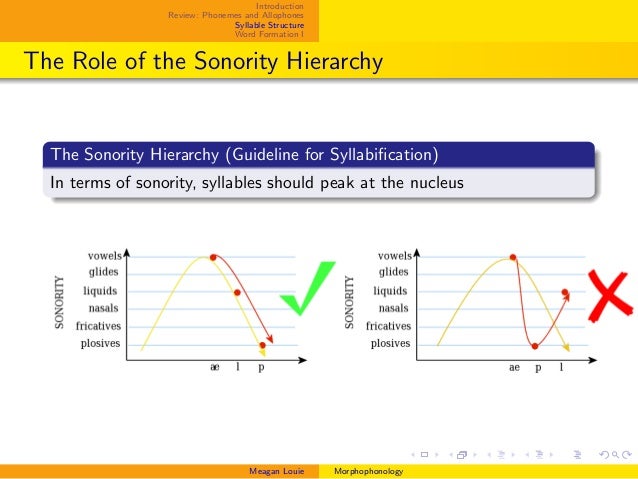

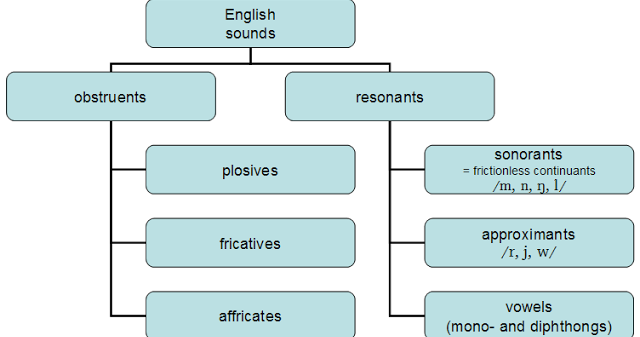

The cluster /kw-/ has a large distance of 6 (voiceless stop (value of 7) - glide (value of 1)). For example, the cluster /sn-/ has a small sonority distance (voiceless fricative Steraide's value of 4) - nasal (value of 2)) of 2. If a child's system included clusters with a small sonority distance, that implied the presence of clusters with a large sonority distance. She identified an implicational relationship between clusters with small sonority distances and clusters with large sonority distances. In 1999, Gierut applied this principle to treatment. The most sonorous sounds are vowels (0), followed by glides (1), liquids (2), nasals (3), voiced fricatives (4), voiceless fricatives (5), voiced stops (6) and voiceless stops (7). In 1990, Steraide assigned relative values to each sound class, indicated in parentheses. Linguists have identified the relative sonority for different sound classes. The greater the sonority, the wider the mouth is and the more vowel-like a sound is (Barlow, 2000). Sonority is the inherent loudness of sounds relative to one another. It dictates that onsets (word-initial sounds) must rise in sonority and codas (ending sounds) must fall in sonority. The Sonority Sequencing Principle for Clusters was identified in linguistic research.

However, there has been some exciting research that would be applicable to these students and others who have difficulty with clusters. If the child has a limited phonemic inventory, this would not work. For example, if a child is taught /spl-/, then he/she should already have /p/ and /l/ in his/her phonemic repertoire. Research has demonstrated that it is most efficacious to treat three-element clusters to effect change throughout a child's system (if the child has the second and third consonants in his/her system already).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)